Hi, I’m Kate. Ask an Author is a free newsletter providing advice and support for authors at all stages of writing, publishing, and hand-wringing. If you know someone this applies to, you can forward them this email and encourage them to sign up. Have a question? Fill out this form and I’ll answer it in a future response.

Dear Kate,

I’ve always been a pantser, but if I’m being dead honest, I also always get to this point in my manuscripts where I’ve got so many things to clean up that it becomes really hard to figure out what comes next or how to solve these plot holes I’ve written myself into. I want to start a new project from scratch and try something new this time. I know you’ve mentioned outlining in some of your other responses, and I want to give it a try and plan more of my book idea in advance. But this is so different for me, I’m not sure where to begin!

How do I start outlining? How do I make one and then use it? I’m nervous that it won’t be helpful, or that it will make it harder to draft the story, not easier. But really, it’s that I’m thinking to myself “Let’s start with an outline!” but I’m not actually sure where to begin.

- Can a Pantser Change?

Dear Pantser,

Welcome to the dark side! Or, what I should say is welcome to the light. You’ve identified a stumbling block in your drafting process, and now you’re looking to shake things up and see if a new approach can help. This is, fundamentally, what writing is all about. Trial and error, developing new skills, and figuring out what works for your brain and your books and your process.

I can’t say whether writing an outline will make writing easier for you. It might not! It’s not a Band-Aid or a magic pill and it doesn’t do the writing or the thinking for you. (Alas.) What I can say is that in my own writing journey, pre-writing and planning in advance have been the difference between sprawling projects that ultimately go nowhere (RIP), and books I can actually finish and that have a shot at getting published. Not every outlined book will be a winner, but starting with some solid planning under my belt (vs. flying by the seat of my pants, or pantsing it—ie, being a “pantser”) is one surefire way to stack the odds more in my favor and make sure I’m starting with a strong premise and a story that has legs.

But I don’t have to convince you of the value of planning. You’re ready to try it, just not sure where to begin. If you ask 10 people how they outline, you’ll get 10 different approaches. Here’s how I tackle the process, although it changes from book to book as I check in with myself about what I think I need, what feels right, where the problem spots are, and how I think I can address those shortcomings.

Thinking. I know this seems obvious. But so often we can be quick to dismiss thinking time because it doesn’t lead (directly) to words on the page. It’s not quantifiable. And it can be easy to use thinking as a productive procrastination tool, giving ourselves permission to not write, or to put off writing, because we’re “thinking.” Don’t do this!!

By the time I start writing an outline for a novel, it’s probably been percolating in the back of my mind for six months, maybe a year, maybe more, while I’m working on other things. A scene, a character, a question—something that hasn’t let me alone for so long that I can’t ignore it. Maybe you have this idea already. Maybe not. I just want to be clear that the process begins before you write a single word, and to honor and value the time you spend thinking as a meaningful part of this planning.

Pre-writing. Before I start writing an outline, I need something to, you know, write about. Maybe this is the stage you’re at, where you have an idea (you’ve done some thinking) but you aren’t sure what to actually put in the outline. Here’s where I do a whole bunch of writing before I even start in on outlining.

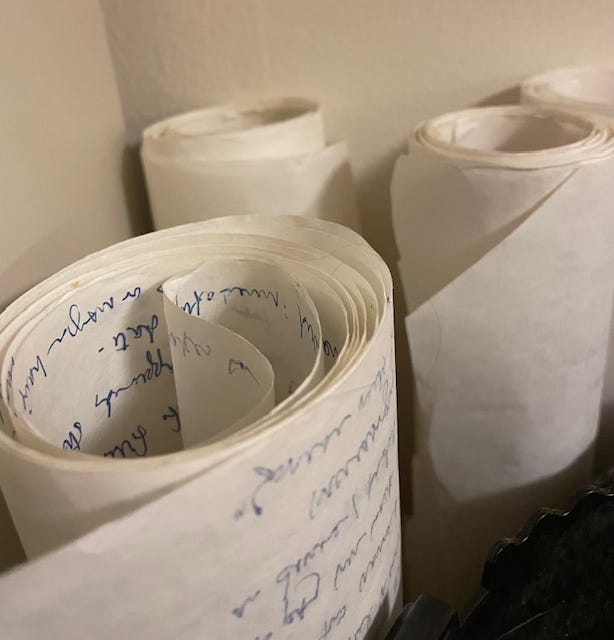

I don't start off trying to write something Legitimate and Important. That’s way too much pressure. I just start by getting to know my book better. When I have an idea that won’t leave me alone (Step 1), I start to press on it. Ask it questions. Test it out. I jot down notes, scraps of ideas, whatever comes to mind. I often do this in a notebook instead of on the computer—but not always. I often use a large sheet of butcher paper spread across the floor or a table so I can see all of my thinking in one place—but not always. Most of this early writing won’t make it into the manuscript, or even the outline, but that’s okay. Sometimes you just need to find a starting point and write something—anything!—because how else are you going to get the ball rolling unless you first give it a shove? Physics applies to writing, too, and if we stay at rest we’ll never get started.

In my novel that’s coming out next year, GREENWICH, my very first bit of writing, before I had enough to even start in on an outline, involved a girl driving with her aunt and passing by roadkill on the side of a rural Connecticut road. In the actual book, now the girl and her aunt are in the car when they spot a dead deer on the aunt’s expansive property. It’s a pivotal early scene that sets the tone for the whole book, but it’s nothing like that initial bit I’d envisioned. I’m working on a new novel right now, and the first scene I drafted (on my phone, on the subway) involved a woman fighting with her roommate before she moves in with her boyfriend. In the actual manuscript, there’s no roommate and no fight—my main character already lives with her fiancé. Sometimes the pre-writing will become important. Sometimes it’s just a stepping stone to get you elsewhere.

Identify the Major Plot Points. Now you have an idea, you have notes and some more filled out thoughts, you’re feeling itchy and antsy and ready to start building a novel. At this stage, I have my main characters and some ideas of the basic situations they might get into and the choices they’re going to have to make. Next, I try to turn this jumble of ideas into a list of key pivot points that are going to occur. This could be the inciting incident, the midpoint, some other turning points, the climax, maybe the resolution—or maybe not. Outlining doesn’t mean you have to know every last detail before you begin. Everything in an outline is hypothetical, anyway, until you actually start writing the thing. The goal here isn’t to be perfect—it’s to give yourself the best head start that you can.

I think of approaching an outline as starting with the biggest picture stuff and then gradually working my way in until I get more and more detailed, until I’m so granular that I might as well just start writing. But first: What’s the overarching idea of the novel? What’s the main thing I’m working toward? What are the biggest building blocks that will lay the foundation for everything else? For GREENWICH, it’s that a teenage girl goes to stay with her wealthy aunt and uncle, an accident occurs, her loyalties are tested, and she makes the wrong choice. My sense of the novel started with these huge blocks. Once I had those elements in place, I started thinking about how to get from A to B to C, and what else should occur along the way. That’s when I started jotting down more things in my notebook—scenes I wanted to happen, issues I knew I’d need to address, bits of backstory I thought I could work in somehow, any and all ideas I had that might fuel this central narrative.

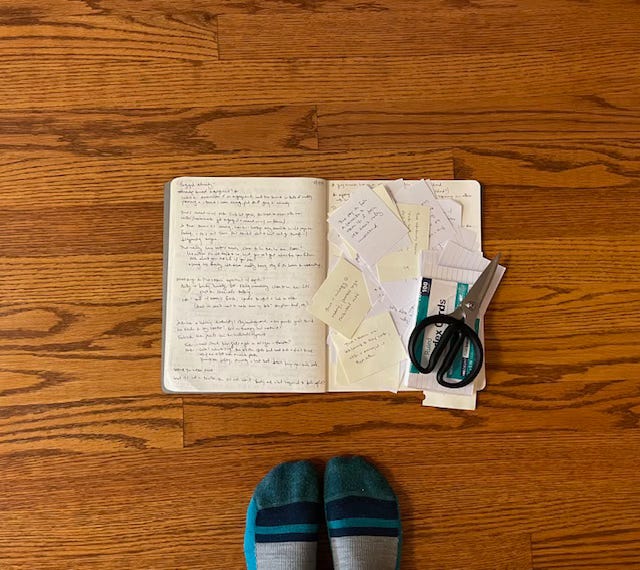

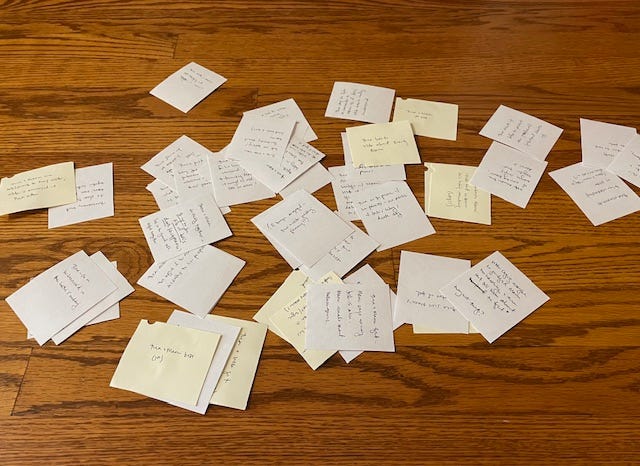

Make a List. (My secret weapon = index cards!!) Now that I have these main ideas in place, I want to start narrowing them down and getting them organized. I have tons of notes, but they can feel overwhelming and all over the place. So I take those notes and distill them down into a monster list of everything I know about the novel so far. This can be plot points, and it can also be emotional pivot points along your character’s journey. No matter what your book is about, there will be moments and touchstones along the way—things you know you want to cover. Write all that down. Don’t worry about the order yet. That comes next.

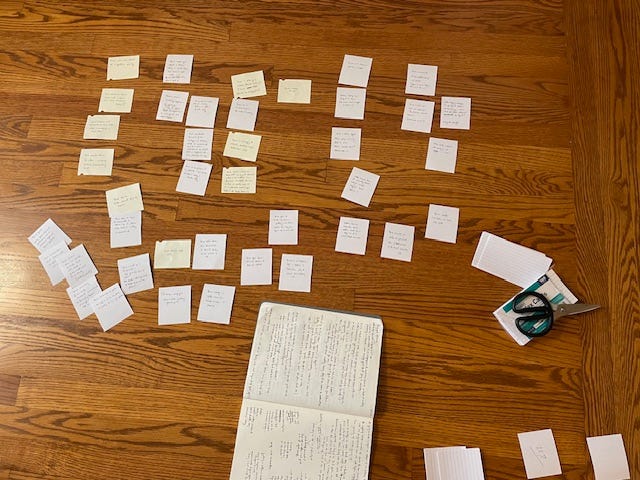

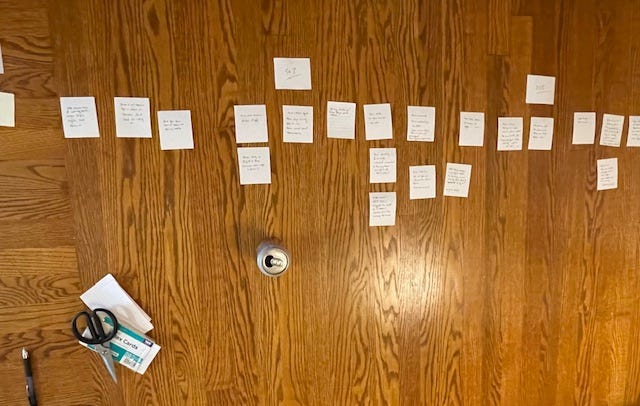

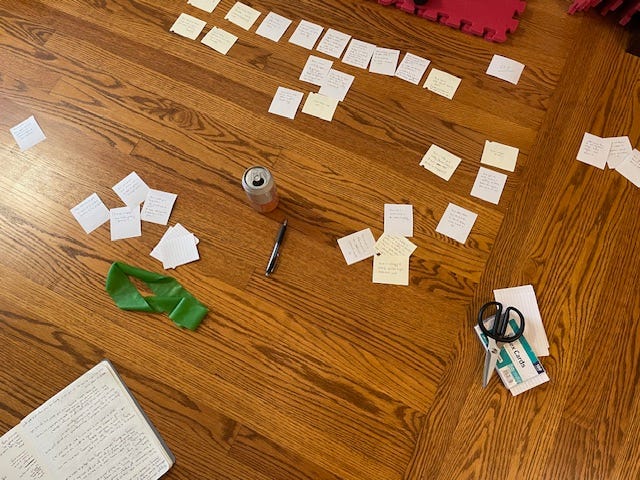

The major “aha!” moment for me was when I started doing this on index cards. I put all these ideas on cards—one idea/plot point per card—and then I literally dump them on the floor and start arranging them. This way, I’m separating out Step 1) identifying the key ideas from Step 2) putting them in order. I’m winnowing down all of my notes and thoughts into something more organized. And I’m seeing how all the pieces connect—how this one moment will lead to something else, and how the consequences of that choice will carry through for all these subsequent situations. In GREENWICH, I knew, for instance, that two characters were going to sleep together, but I didn’t know when in the narrative that would happen. So I wrote that on a note card, and then got to work figuring out where that card should go—what comes before it, what comes after, and why it has to occur at that one key point in the story and not anywhere else.

Using index cards lets me physically see and arrange my material so I can put all these events and ideas into an order and make sure my book has rising tension, a coherent narrative, and a clear beginning, middle, and an end. Again, I’m looking for the touchstones, and then the blank spaces that need to be filled in. Where I find a hole, I figure out what I need to add there. Where I’m repetitive, or out of order, I cut and rearrange. It takes TIME. This is weeks of work. But it’s worth it. By the time I’m done, I have a whole novel laid out from start to finish (ish).

Write the actual outline. By the time I’m done working with my index cards, I have a basic outline. I will often then take this working outline and write it out. Yes, it looks like rewriting, because I already have my points in order in the note cards. But repetition is your friend. The more times I touch my outline and make myself see and articulate it from start to finish, the better I get to know my book and all its ins and outs. I know the outline so well I almost don’t need to look at it anymore—but I always have it to reference as I work.

Your outline may change as you write. Mine always do. An outline isn’t a promise, and you aren’t beholden to it. No one is ever going to read it but you. If you start writing and a great idea pops up—run with it! Usually I wind up writing a second outline when I’m about halfway through the first draft and realize so many things have changed, I need to revisit all my planning. In GREENWICH, I had one plan for the last third of the novel and then scrapped it completely to try again. When I deviate from my outline, I stop to ask myself whether the outline is right, or the thing I’m writing. Sometimes I change what I’m writing to match the outline, because I think the outline is the path to follow and I’ve been veering in the wrong direction. Sometimes I change the outline because I’ve found a better direction. You can use the outline as a tool to help you get to know your story better. All that time thinking will only help you along the way.

And if you’ve already written something and are wondering how to reorganize it, I have a post on The Reverse Outline, a strategy that’s saved me more times than I can count:

The Reverse Outline

Dear Kate,

In one of your newsletters, you mentioned a reverse outline. Can you say more about what that is?

- DJ Casper

If you find outlining cramps your creativity and doesn’t work for you, don’t do it. If you discover a different way to get your outline rolling, by all means do that instead. I hope something in here might be a useful tool for you, Pantser, as you experiment with a new process. No matter what works or what doesn’t, keep going!

Kate