Hi, I’m Kate. Ask an Author is a free newsletter providing advice and support for authors at all stages of writing, publishing, and hand-wringing. If you know someone this applies to, you can forward them this email and encourage them to sign up. Have a question? Fill out this form and I’ll answer it in a future response.

First, some housekeeping: Welcome, new subscribers! With the upheaval over on Twitter, many new folks found their way to Ask an Author this week. So glad you’re here! Take a seat, settle in, get comfy. You can look through the Ask an Author archive, including questions like “Should I quit querying and self-publish instead?”, “How do I write a synopsis?” and “Whose feedback should I take?”

These are all questions that came directly from readers. If you could pick an author’s brain, what would you ask?? Now’s your chance! The form to ask your q is anonymous. The Substack is free. It’s fun and meaningful to me to hear from you and feel like we’re thinking together and making writing and publishing a little less solitary. I hope it’s fun and meaningful for you, too.

Thank you for being part of this growing community and for helping to spread the word!

Last time, I received a question chock full of great stuff to dig into, so I divided it into three parts.

Read Part I: How to Write Faster (without sacrificing quality) here.

Read Part II: How to Write on a Deadline (without panicking) here.

This is Part III: How to Tackle Large Projects (and see them through).

The original question:

Do you have any tips for how to write faster, or make myself write on a deadline? I find I struggle with bigger projects that take longer to complete. I get overwhelmed, change my mind about what I’m working on or what I want it to be, and often wind up walking away. I want to understand my own writing process better, so that I can try to create some systems that I hope will work for me.

- Under Pressure

Dear Under Pressure,

We’ve looked at how to write faster and how to write under a deadline — which was my most-opened newsletter by a LOT, so apparently everyone is feeling the stress! This week I want to look at the third part of your question, about “bigger projects that take longer to complete.” How to choose a project, how to stick with it, and ultimately: how to finish.

A large project is a series of small projects strung together to make something bigger.

Of course that’s not entirely true—there’s a thingness to the project that makes it more than the sum of its parts. A novel is not merely a collection of individual pages. A movie isn’t one scene shot after another with no connection between them. But for the sake of STARTING the project, a book gets written page by page, paragraph by paragraph, word by word. Everyone has different strategies, and I’m not here to say THIS IS HOW YOU DO IT or you’re WRONG if you have another approach. But if you’re struggling with how to tackle something larger than you’ve done before, here is how I think of it. I’ve written eighteen novels (!!), one 292-page dissertation (also !!), and co-edited an academic book on YA dystopias that took years to complete, but taking that first leap into long-form writing was a big one. (Not all 18 of those are published, but I sat down and wrote them, so for the sake of this exercise, I’m counting them!) I’m using the example of novels here because that’s what I write, but it translates to pretty much anything, I think.

I’m an outliner, in that I want to know roughly what I’m getting into before I start it. I want to know what I’m writing toward, so that I can get there. But when I start a novel, I don’t know yet what it’s really about. I may know the scenes that happen, but I don’t know its heart, its core, its guts. Because I haven’t written it yet! I write to discover what I’m writing about — and then when I finish that draft, the process of revising (and revising, and revising) is (for me) about figuring out what the book is truly about and bringing that to life. If you’re sitting down to write a book (say) and change your mind about what’s going on or what you’re trying to say, that’s a reason to keep writing — to keep pushing toward the thing that still feels nebulous and out of reach. You don’t have to pre-decide what you’re writing before you write it. Anything you’re dreaming of before you write it is only hypothetical, anyway. You can’t know the heart of something that doesn’t exist.

You say, Under Pressure, that you get overwhelmed and change your mind, but what I hear is someone who isn’t giving themselves the time and space and latitude to be uncertain. Which is to say, the time and space and latitude to *actually write.* If you expect a strong first draft, a draft that isn’t full of holes and changing its mind and wrestling with itself and pushing and straining and splitting into different directions, then yeah. You’re going to be disappointed, frustrated, fed up, and ultimately quit. But what if you embrace that overwhelm as part of the process, as a sign that you’re doing the thing?

Writing is hard. If you’re finding it hard, that doesn’t mean you have a bad idea or bad execution or are bad at writing and should stop. It just means you’re writing. Matthew Salesses wrote an incredible pep talk for NaNoWriMo about how writing a novel requires you to descend deep into the valley before you can climb your way out. You have to recognize that what you find on the other side of that valley—in the draft you ultimately write, and the manuscript you ultimately produce—is going to be different than you’d imagined. Ann Patchett describes this process as running over a butterfly with an SUV. The butterfly is the perfect, beautiful thing you imagine before you start writing. The dead husk left behind is your book. Bleak! But I appreciate the reminder that the distance between the thing in your head and the thing on the page is also called writing. There will be disappointments.

There will also be incredible surprises.

The summer after I graduated from college, I started writing a novel. I’d never written a novel before. I’d only written like three short stories in my life. I’d been writing and publishing poetry, but I always wanted to write a novel and so I got to work. I was a “good” writer (or so I’d been told) and I’d always been “good” at tackling what I set my mind to. I was excited to be “good” at my first novel, too.

I’ll spare you details, but I managed 200 pages (which is a lot actually, I wish I’d given myself more credit!) and ultimately hid the mess in a drawer. I’ll come back to it, I decided, when I know how to write a novel.

I started a PhD in English. I kept writing poetry. But that novel was the tell-tale heart under my floorboards, thumping away. All the time I spent teaching and writing academic scholarship was time I wasn’t getting any closer to my goal of writing a novel. Somewhere in the middle of my grad program, I finally dawned on me: not writing a novel wasn’t making me any better at writing novels. The was never going to be a time when I knew how to write a good novel. I was going to have to suck it up and write something terrible first. :/

I was overwhelmed by my workload and unhappy and realizing I maybe didn’t want to be an English professor or a poet and afraid I’d never write something I loved. So I embarked on a project in which I decided I’d write a novel but only for the sake of seeing if I could push through all the sticky parts and the self doubt—if I could make it to the end of a draft. I gave myself parameters. I had to write every single day. I could only write for one hour—no less than that, but also (and this was key!) no more. I couldn’t go back and reread anything I’d written. There was no outline, no plan. The point wasn’t to write anything good. The point was to write.

In just under a year, I wrote 400 pages of a YA sci fi novel that will never, ever see the light of day. There was no point revising it — it wasn’t going anywhere. But I learned that I could string together 400 freaking pages with a beginning, a middle, and an end. I learned that small acts can accumulate into something much, much larger. I learned that by making myself always have one extra hour in the day, I actually had a little more time than I’d realized. Writing that novel gave me the confidence to feel like I could write a dissertation, because now I’d written something really, really long. Writing, revising, and polishing my dissertation showed me I could write an actual novel that I’d stick with over multiple revisions.

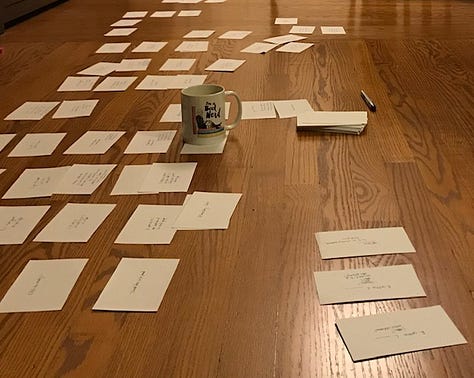

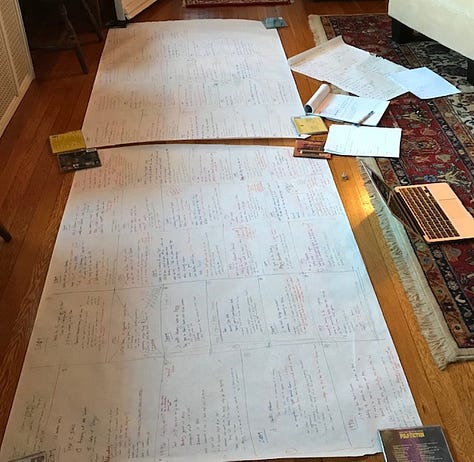

I don’t know if my writing has improved on a sentence level over the years (I mean, I hope so??), but I can definitely trace the change in how much of a story my brain can hold onto at once. I can SEE an entire novel in a way I couldn’t before I started practicing at doing just that. I’ve also figured out more tricks and tools to help me in the process. I plot whole books on index cards that I arrange (and re-arrange) on my floor. I brainstorm in color-coded outlines so I can follow each character, each time period, each section of a plot all at once. I use large pieces of butcher paper so I can trace the entire plot of a novel on one page and look at it all together. I re-outline, searching for redundancies, non-sequiturs, and plot holes. I make reverse-outlines distilling what I’ve already written. But I didn’t do any of this for that first YA sci fi. I just wrote, so that I could see what happened not just in the story but in ME between the first page and what became the last.

It’s hard to sustain the motivation of “I’m writing a novel” over literal years, because every day you write is still another day you haven’t finished that novel. But if you say, “I’m writing X words” or “I’m writing for X amount of time” or “I’m writing X scene” or “Now it’s time for X chapter,” you have progress you can track. You have a thing you’ve accomplished and can feel good about. You can see the project taking shape — not its lack (“why am I still not done yet?!?”) but its growth (“today I have 50 more words than I did last week!!!”). This is the same thing I suggested for meeting a deadline: breaking a project into its composite parts so you can tackle each one without always feeling the largeness of the impossible task breathing down your neck.

“Writing is like driving at night in the fog. You can only see as far as your headlights, but you can make the whole trip that way.”

E.L. Doctorow, Writers At Work: The Paris Review Interviews

A large project is, as Doctorow says, like driving in the dark, taking only the turns you can see. It’s like climbing a staircase: you get there step by step. It’s like training for a marathon, which you build to through a series of shorter runs only gradually increasing your mileage. It’s eating the elephant one bite at a time. Building a house through each layer of brick. It doesn’t happen all at once, and most of the time, you can’t see the whole through its parts. You can’t see anything that resembles a forest when you’re groping your way past each tree.

Revising, fixing, improving, making something good — those are later tasks for a later you. The purpose of a first draft is to tell yourself the story. Its only job is to get to The End. If you make a new discovery partway through that shifts your direction, that’s great— you can keep going anyway! (See: What Comes After Draft 1?) There comes a point in every single novel when I think, this is crap, I am crap, I should stop throwing good time after bad and just start something else. The other thing will be easier, better — it won’t feel like this. But I know, because I’ve been here time and time again, that the shiny new thing will inevitably become just as challenging as the old mess I’m currently stuck with. Don’t let yourself be seduced by the false promise of the easier thing. It seems easy because it hasn’t been written yet. Eventually you’re going to figure out the plot hole, smooth the stilted dialogue, round out that flat character you’re frustrated with. But only if you don’t walk away.

There are practical ways to break a larger project into manageable chunks, think through your deadlines (internal and external) for completing each chunk, and create the conditions to help you sit down and make each of those chunks happen. In all of these steps — and in each part of my responses — the most important thing is to not give up too soon. I try to always stay a few steps ahead of my doubt, so it can’t quite catch up to me. I need to be far enough into the draft of a novel that by the time I want to walk away from it, I’ve invested so much time that I also can’t bear to quit. You’re flexing a new muscle here, Under Pressure, and it will get easier the more you use it. But it will never be EASY — and that’s okay. The difference between a person who writes a novel and a person who doesn’t is time and persistence, not talent or skill.

Stick with it.

Kate

p.s. Happy Thanksgiving to all who celebrate, and enjoy some well-earned rest time. Next up will be a question about professional jealousy, ooOOOOOOOoooooo. Subscribe, stay tuned, and let me know how I can help!